You’d be surprised at how often we find mistakes at the beginning of projects that, if not caught, would put most of a client’s insurance coverage at risk. Clients frequently ask us to review their controlled insurance programs (often referred to as “CIPs” or “Wrap-Ups”) before implementing them. Brokers do much of the heavy lifting in structuring these programs, but many of our clients like to have coverage attorneys review them for some nuances that lawyers who litigate coverage issues will pick out. The issues get pretty esoteric, but some esoteric issues can be worth a lot of money. Lately, I’ve been seeing one particular type of exclusion in Wrap-Ups that, if it remained and were enforced, could jeopardize much of the coverage the client thought they were buying in the Wrap-Up: a “Cross-Suits” exclusion.

Under a Wrap-Up, the owner (under an “Owner Controlled Insurance Program or “OCIP”) or general contractor (under a Contractor Controlled Insurance Program or “CCIP”) and all contractors and subcontractors of every tier are named insureds under certain project insurance, typically general liability and workers compensation. When properly administered, a Wrap-Up program can increase project savings, reduce litigation, provide more complete coverage for completed operations, increase Minority and Women Business Enterprise participation, among other benefits.

But Cross-Suits Exclusions are children of a different type of insurance set-up, a more traditional program where individual contractors and subcontractors buy their own insurance and some are required to make others additional insureds. This exclusion precludes coverage for claims brought by one insured against another insured. A typical Cross Suits Exclusion provides: “This insurance does not apply to: . . . Suits brought by one insured against another insured.” These would, for example, avoid the “moral hazard” of a parent company suing its own subsidiary to trigger liability coverage.

But in a Wrap-Up, this doesn’t make any sense. Remember, in a Wrap-Up, the owner, general contractor and all subcontractors are all named insureds. So a Cross-Suits exclusion would bar coverage for any liability the general contractor may have to the owner for losses arising from it or its subcontractors negligence. That’s a significant part of the coverage that an owner would want its contractor to have on a GL policy. If a Cross-Suits exclusion remained and were enforced, the only liabilities covered would be to third parties–parties that have nothing to do with the project.

A similar limitation is created when a Cross Suits Exclusion is included in a CCIP. Although in that circumstance there may be coverage for a contractor’s liability to the owner (if the owner is not a named insured), contractors will not be able to trigger coverage for their own losses arising from the negligence of another contractor/subcontractor on the project. For example, the general contractor will not be able to trigger the Wrap-Up program for losses it incurs as a result of its subcontractors’ negligence.

This is just an example of an exclusion that plainly doesn’t belong in a Wrap-Up program, but that we’ve seen almost inserted in them recently. Make sure to have a reputable broker review your programs before implementing them and consider investing a small amount to have a coverage attorney review it. Prior planning prevents poor performance.

Gravel2Gavel Construction & Real Estate Law Blog

Gravel2Gavel Construction & Real Estate Law Blog

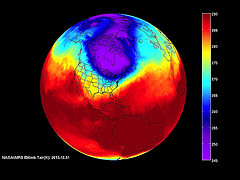

from the extraordinary weather disaster during the first two weeks of 2014. Among other things, the big chill froze pipes and sprinkler systems, interrupted chemical manufacturing and disrupted transportation systems, causing extensive property damage and business interruption as a result of freezing temperatures.

from the extraordinary weather disaster during the first two weeks of 2014. Among other things, the big chill froze pipes and sprinkler systems, interrupted chemical manufacturing and disrupted transportation systems, causing extensive property damage and business interruption as a result of freezing temperatures.